This is a big story, a true story, and a companion piece to the new Landlady album. You don’t need one to enjoy the other, but I hope you enjoy both all the same. – Adam

image by Case Jernigan

Merch, Wind & Fire

(or Stand By Your Van)

by Adam Schatz

—— —— —— —— —— ——

<I>

I’ve driven a minivan my entire life. Or maybe it’s driven me. Together forever, to and from regular school, to and from Hebrew school, to see a friend in another town, to get a burrito and make it mine, always with the radio on, long before I knew about Jonathan Richman, but maybe growing up in New England means some things don’t have to be taught to you. Tell that to the teachers whose names I can barely remember. But school is where I met friends and joined bands and most of our time was spent in cars.

In the minivan and on the radio, great songs woke me up. Great songs smashed me to bits. They made me want to start a band. In the minivan and on the radio, I heard Queen and the Beastie Boys and Paula Cole, Outkast, Slick Rick, Fastball and the Barenaked Ladies and it was all right by me. Before I could drive myself, I landed at my first concert, by accident and alone. I was thirteen and had waited outside in line all damn day at an Outkast autograph signing at Strawberries records in Cambridge, Massachusetts, flying solo save for the MiniDisc pumping home-made-radio-sampled mixtapes into my ears by way of wrap-around cut-the-backs-of-your-ears headphones. After three hours with a growing line behind me, a representative from JAM’N 94.5 alerted us that Outkast’s plane was late and they would have to skip the signing in order to make their concert that night at Boston College. I was betrayed by a representative of the radio medium that I had treasured so dearly. Three hours of waiting alone all for nothing. Bad luck.

The rap radio representative announced that everyone who showed up to wait would be given a free poster, news met with boos. The rap radio representative continued and shouted that the first 50 people in line would be given a free ticket to the Outkast show that same night. I knew I was in: I had arrived so very early, because my “Stankonia” translucent orange vinyl wasn’t going to sign itself. The rap radio representative walked down the line and slapped on a paper wristband, the first in a long, rich legacy of paper wristbands that sucked my arm hair into its clenched seal. I sprinted inside the Strawberries and called my mother to ask if I could go to the rap concert. She approved, as long as I submitted to a midnight curfew, for it was a school night, and I had to be well rested for math class the next day with Mrs. Whatshername. I was dropped off at Boston College and eventually found the venue (gymnasium) after asking a seemingly 12-foot-tall college girl “are you going to the Outkast concert?” Xzibit opened, Outkast smashed, my mom picked me up before it ended and I’ll never forget it. The power of performance, the true joy of being floored by great song after great song, bowled over by the architects of it all, right in front of me. What else was there to live for? I never did get an autograph from Andre 3000 or Big Boi, but if I left that night knowing what I wanted to be. Maybe luck can be bad and good at the same time.

Before I was old enough to sit behind the wheel of a minivan, I started a band, a proving ground to try to write great songs. We tried and tried and again, my friends and I. We wrote songs that made sense to us and rehearsed them into submission. We dreamed of making rock & roll memories beyond the confines of our zip code.

Being in a band is a consecrated excuse to goof off at a regularly scheduled time in a small space. It’s a way to improve with people you like. If done right, you can see in real time how your ego interferes with improvement and muddles relationships, and you can be offered the chance to toss that aside in the service of great songs. How wild. And if the songs aren’t great, you still get to play really loud and stand really close. Being in a band is an immediate community, partnerships on a path to navigate planet Earth and the inevitabilities of growing up. Before you can drive yourself. Before you’ve ever spilled a beer or eaten mandatory green room hummus.

In pursuit of rock and roll memories, we recorded our songs onto a friend’s desktop computer and made our own merch. Bask in the unromantic design of that noun: merch. Now for a bit of inside baseball: on a computer or phone, “merch” will always auto-correct to “march.” And that’s because the word is dumb. Short for merchandise —hey, wake up!— “merch” paints the illusion of a band as a shopping center rather than a nucleus of art and relationships. Still, as kids with dreams it was obvious that we had to make the march (fuck!) to sell at the gig once we booked the gig so that meant powering forward with creating the most breakable CDs and T-shirts printed on the scratchiest fabric ever discovered. Should you fall into a time machine and wish to blend in with a rock band of youths, here’s the instruction manual:

Step One – Go to Staples

Step Two – Dream of one day owning a three-hundred-dollar office chair

Step Three – Ogle the printer cartridges

Step Four – Get the stuff you need in the paper goods aisle

Step Five – Leave Staples

Step Six – Once at home, begin an assembly line with your ding-dong buddies in the basement where you will burn a spindle’s worth of CD-Rs containing three of your best songs and two more as well. Use $150-worth of color ink to print sticky labels for the discs themselves. Carefully remove the circular sticker and with utmost precision slowly lower it onto the CD-R. Twitch at the last second to create permanent wrinkle on the surface. Repeat 99 times. Realize there might be a few blank CDs in some of the cases, and forget to check. You are now ready to commence with the creation of the rock & roll memories.

Our first tour ever took us to a venue in Bath, Pennsylvania named Brenda and Jerry’s. It was a music store by day, all-ages venue by night. Brenda let us sleep on the stage, and came back out around midnight to play the organ for us. We woke up at 10AM when the store had opened and a local lady came in asking if any of us shirtless teens knew if they sold tambourines there.

Four people came to that show, but that story is eternal, lodged into my brain for keeps, probably where my times tables used to go. Sometimes luck is good and bad at the same time.

I wrote more songs and started more bands and went on more tours and it all was preparing me for this moment, as my current band of current ding-dong friends is attempting a very dumb drive.

Landlady, my present-day band of modern grown-ups who are all supposed to know better and have employment with benefits, is headed from Seattle to San Francisco on a tour where we play shows for real people in America’s best cities, and twelve others as well, where the green rooms are closets and the hummus flows like wine. We are driving in a minivan that’s sufficiently weighed down by an optimistic tonnage of merch: three albums’ worth of LPs, CDs and T-shirts that don’t hurt when you put them on. How far we’ve come! And although this drive is simply too long, I’m still here making music with my friends, and I still feel lucky because of it.

<II>

Good luck is built to be taken for granted. My first minivan was the family minivan, a maroon Toyota Previa, an XXL eggplant with all-wheel-drive boasting a six-disc CD changer, the kind of CD changer we’ll tell our grandkids about when we drag them to the Museum of Esoteric Nonsense Of The Past. I was lucky to be allowed to drive that car, I was lucky every time I turned the key and it ran, and oh how it ran, for over 200,000 miles around and around the USA, until it ran straight into the ground.

I was unlucky when my minivan died and I had just filled the gas tank.

But life goes on as it insists on doing, and soon a new minivan entered my life, a rust-free granite beauty that promised me it would live forever. I named it Scott, a name that I wished was my own for a brief period of elementary school when I grew frustrated with the total five Adams in my class.

And now, my beloved Scott is carrying my band down the western side of these United States on a drive that could only be described as just a little extra-dumb. But poor choices are a well known side-effect of Tour Brain. Sleep is lacked, priorities get slushed about and you begin to see the gas station attendant’s head as a cat hair-free Tempur-Pedic pillow. We’ve just played in Seattle and have two days off before our next show in San Francisco. And while that thirteen hour drive seems silly to attempt all at once with two days in between, we know that we have a great place to sleep once we reach San Francisco, where a close friend’s mom will feed us and maybe we can become one with the television for a night. Maybe we can go for a run or eat a burrito the size of an adult bicep with the digestive confidence of knowing that we won’t have to perform later that evening. Those maybes will sustain us. A true day off is so rare and now we’ve got one clean in our sights. It simply makes the most sense to get to San Francisco as soon as possible. Tour Brain tells us we must, so we are. And we’ve done long drives like this before. We aren’t complete morons, after all.

Bad luck wakes up early with us on the day of this extra-dumb drive, and provides gridlock traffic between Seattle and Portland. After five hours of snail’s pacing, we stop in Portland to grab lunch and lose ten more minutes waiting for a comically long train to pass, a train that is surely carrying some esoteric nonsense of the past, like coal, or MiniDiscs.

After grabbing our sandwiches we wait again on a drawbridge, allowing the Slowest Barge in the Pacific Northwest to pass underneath, and I have to consider what we’ve done to deserve this. Our day is not going as planned, but in the repetition of tour, sometimes the worst that can happen still isn’t all that bad. On tour, the worst parts of life fade back into the normal world that we’ve left behind and pause while we coast from show to show, from green room to green room, hummus to hummus, dust to dust. On tour, the worst of life could only be a series of early wake-ups and surprise traffic, totally manageable on the grand cosmic scale. Real life churns on, as it insists on churning, but we’re safe in the van, an insulated temple of gear, merch, snacks, jokes, and farts.

Death is the exception that proves the rule. At quick glance death feels like the opposite of life, but ultimately death is the classical result of life going on. Forever intertwined. Bummer. And so, even on tour, life occasionally goes on at such an aggressive clip that I have to pay attention, and a dark sourness can chisel its way in through the sliding door of the minivan.

A million years ago, when I first moved to New York City, I joined a band called The Teenage Prayers, a band named stolen from a Bob Dylan song, a band name that would lead Christian music fans to become frustrated when they learned the band was in fact full of grown men who didn’t believe in God. Well, except for me, I was eighteen. The band was Tim and his brother Terry and their cousin Kyle and their buddy Kyle (two Kyles I know, but don’t worry, they don’t come back in this story, so go ahead and forget you ever heard the name Kevin. See? It worked). Terry is who we’re going to focus on, because Terry is no longer alive. Everyone else will have to wait their turn.

The Teenage Prayers had lived longer than me, drank beer in their smelly practice space better than me, and drove a shittier van than me to shows that people never knew were happening. They wrote great songs. I learned those songs with the gratitude of being let into the club. As we drove from show to show we would listen to the great songs that had been drilled directly into their hearts and forced them to start a band in the first place. Big Star and Randy Newman and Built To Spill and Solomon Burke, I piled those greats onto my growing collection of great songs that had been born in the earlier minivan memories, the songs that rewired my circuits and helped me approach writing a song with the focus and fire that I’d hear in those brilliant architects.

Terry and his family adopted me for my first real tour across the country. They eased me into my life in an unforgiving city where I learned that I could keep making music with friends, even when the sour darkness chiseled in, that I could feel lucky even if the rent was exponential and the bedroom was a basement, that I could keep exploring and chasing rock & roll dreams from radio days.

I had always dreamed of being on the radio. On one tour, The Teenage Prayers performed a set for the radio station at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. We played for thirty minutes while students engineered the recording at the console behind glass, and the set would be broadcast later that day. We sounded great in the headphones and figured the performance would surely drive five to ten additional ticket buyers to our show that evening at Schuba’s in Chicago. When we caught the radio broadcast a few hours later, we learned that due to a technical mishap the students had failed to record the lead vocal, and were transmitting The Teenage Prayers’ instruments and backing vocals only. Just long, drawn out spaces of garage rock guitar and pounding drums with the occasional “it isn’t any good!” and “ahhhhhhh” peeking in above the suddenly minimalist band.

These aren’t the rock & roll memories I thought I’d remember, but I’m glad that they are.

Terry had a tumor in his brain, and it had been there while we played his songs. When a doctor diagnosed Terry’s Brain Cancer, Terry moved back to Ohio to be closer to his folks and receive treatment. It felt like ages, but eventually he got better. He rang the bell and everything. Full remission. And then the cancer came back, playing for keeps this time. In the January of the final year of Terry’s life, I got a phone call from his brother, telling me that this was the year Terry was going to die.

Aside from his busted brain, Terry had an expansive heart and a limited tolerance for bullshit. He worked a job he hated but that allowed him to truly give his guitar the business whenever it fell into his hands, always hanging too low off his bony shoulders. There’s that tension threshold, when technical limitations meet conviction, and certain people can take that collision and channel it into raucous perseverance, a push-through that screams “I don’t know what happens now when I push harder but we are going to find out.” That happened when Terry played the guitar. It happens when the best people play the guitar. Good tension.

He wielded a tattoo of his home state Ohio on his arm. I was allowed to be a part of his world whenever we played loud together. I was able to witness brothers sharing a band, which felt impossible, but when it worked it worked so well, thanks to good tension.

How do you say goodbye if not with great songs? The year Terry was predicted to die, the now inactive Teenage Prayers assembled for one last show, reunited in Columbus and determined to give him a living wake. Terry wasn’t well enough to sing, but he watched among friends as we played and belted his own great songs back at him, in the comfort of a dark rock club, where we could pretend for brief moments in the loudest parts of the greatest songs that everything was going to okay. We played Terry’s favorite songs written by others. We sang “ Everybody’s Gotta Live” by Love and barely got through it. We played “Jump Into The Fire” by Nilsson, and we meant it too, stretching the ending on and on in a room where joy and pain was swirling together like a giant soft-serve that you know is going to make you sick but it’s the summer and you’re eating it all no matter what.

My time touring with these friends who were years beyond me in settling the lands of experience, mistakes, loves and losses, I accepted my good luck that there could be a shared language when you play in a band, a cheat code to cut the line and immediately connect more deeply with those you’re making art with. It’s a different van with different people, but there’s common ground that we ache to gather upon, within the safety of the possibly unsafe van, knowing that if the gas runs out it very well might continue to run on gear, merch, snacks, jokes, and farts.

Terry died while I was on tour with Landlady, and I picked up the phone with a heavy heart to receive the news. I played our next show and did my best to sort it all out within the safe embrace of my loud band. A great song delivered with abandon connects dots in a way that only it can. A band, being a nucleus of art and relationships, is the primal vehicle for delivering those goods. And that’s the vehicle from which I knew and loved Terry. We did our best, loaded out, and knew we’d try it all again tomorrow.

Around that same time, I received another phone call, this time from Nashville. I picked up even though I didn’t want to. By this point most phone calls were bad phone calls. I answered and learned that my friend Jessi Zazu was diagnosed with cervical cancer. I hung up the phone. Two friends, two cancers, in two years. But Jessi was still alive and I was still optimistic. How bad could bad luck get? I knew I would get to see her soon, when Landlady would tour through Nashville on tour in February, the very same tour that has us driving an extra-dumb extra-long drive from Seattle to San Francisco. Over the drawbridge and through the woods, as the rain began to fall.

<III>

Jessi Zazu’s band Those Darlins made their first album in New York, in 2008, with one of my best buds Jeff producing, so I was fortunately roped in for saxophone and keyboard duties and accidentally made some of my best friends for life. It was incredibly good luck, although when you make a friend for life you aren’t told how long their life will last, which is a pretty nasty loophole that I’ve been meaning to talk to someone about.

Those Darlins were a new band and Jessi, Nikki and Kelly had come to town from Tennessee to begin working with Jeff. He called me, describing the silly, wild women sleeping on air mattresses in his apartment and I got over there as fast as I could. They had infectious spirits and hairy armpits and a deep knowledge of old great songs that I had never heard of, including the Carter Family’s “Cannonball Blues” which ended up on the Darlins debut album, recorded largely in Jeff’s basement. Listening to those recordings is hard for me now, I skip around and can’t really finish them, but when I do force myself I can hear the vortex of making records when you don’t know who’s listening and you don’t care, rule-breaking and risk-taking, when good luck brought me into yet another family of confident builders, fearless to fuck up and try again, brilliantly funny and unstoppably caring, when it counted. My standards for who I like to spend time with and make music with have never faltered since the days of buying merch supplies with my ding-dong friends in Staples, thanks to the constant reaffirmations that these people are out in the world, getting through the daily bullshit, allowing life to go on until we find each other. And sometimes we do.

Jessi and I were the closest in age and became very close, very quickly. She was that person who I would send every song I ever wrote to, just to make sure it flipped her switches. We would tell each other the truth. I would ask her about the Louvin Brothers and she would ask me about Charles Mingus. We would laugh, a lot. When I was in Nashville, she would draw me. When she was in New York, I would cook for her. And any time we got to share a stage, I felt lucky.

I didn’t plan on these being the rock & roll memories that I would remember, but I don’t mind that they are.

My minivan is nice because it’s big enough to breathe in and not feel like you’re recycling the air, but small enough to fit into any parking space. If I haven’t sold you on it by now, I’m not sure why you’re still reading. This essay is brought to you by the minivan farmers of America.

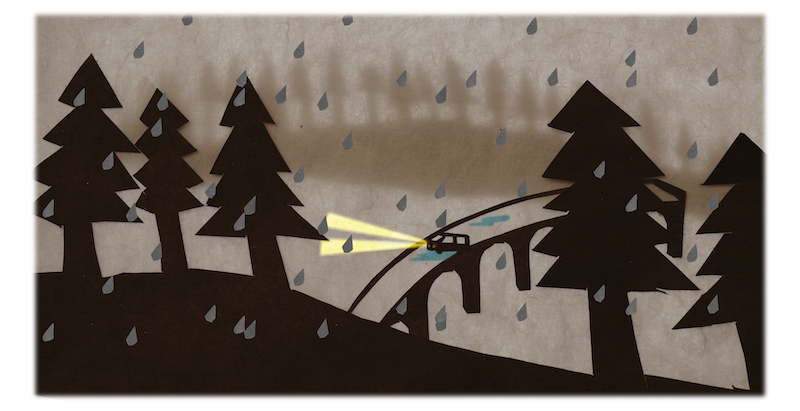

Back in the minivan with Landlady on the just a little extra-dumb drive from Seattle to San Francisco, the barge passes and the drawbridge lowers, and my friends and I cross into Northern California, and as the rain falls harder and faster, our energy drains. We are tired, we are sleepy, this drive is taking too long. We find ourselves pulling over for the third driver switch. We gas up. We stretch. We yell at the sky. This isn’t going to happen without snacks.

I buy some peanut butter-filled pretzels. “This is gonna change everything,” Tour Brain tells me. “Right you are,” I reply. “I love you,” says Tour Brain. “Oh stop it,” I blush. The gas station attendant stares at me while I mutter to myself and his head begins to look like a refrigerator full of some mom’s food. We get back on the wet road and try not to think about how many more hours we have left to drive, in the rain, in the dark. We look up possible hotels but we can’t afford them and they’re all in Redding, where we don’t know any moms. We know that continuing to drive might be risky, but Tour Brain is our co-pilot, so we double down. We know what to do. We fire up the time machine and reach back to the age before we could drive. We begin playing songs from our childhood on Scott the Toyota Sienna’s formidable sound system.

We didn’t invent this trick. It’s a universal rallying mechanism, a short circuit back to the radio days when music was brand new and you didn’t know what hummus was. The great songs that made us who we are, that separate us from and connect us to each other, that’ll drive the van even when we’re asleep at the wheel. “Right on!” Tour Brain agrees. “Swish swish swish” say the wipers on the van. And we’re off, officially powered by a Third Wind. The New Radicals, Weezer, Stone Temple Pilots, Spin Doctors, Ska, Ska, Ska! Songs that may be embarrassing to listen to now, but were truly great when we first heard them. And it’s working, oh how it’s working! We are spell-broken, wide awake, jumping into the fire and ripping through the rain, so certain that we’ll make it to the Bay Area by bedtime. Song after song, we carry on, yanked from the days of hiding the parental advisory sticker on the Outkast album with your thumb at the record store so your parents would let you buy it. Songs from when you’d compare notes to see who had stayed up the latest.

And now we are putting those skills to the test, all of us staying awake, windshield wipers raging, Dave Matthews shouting some esoteric nonsense over a splash cymbal and an acoustic guitar.

Someone puts on “Flagpole Sitta” by Harvey Danger, a band from Seattle, where this dumb drive began. You know this song. Everyone does. And if you don’t (you were born before 1940 or after 2005), you likely have another song in your life that fills up the same space. A foolproof song to shotgun you back to the time of carpools and cargo pants while feeding you pure satisfaction in the present tense. An inarguably great song that can be played absolutely everywhere, and you don’t mind hearing it for the three thousandth time. Scientists in Atlanta call it the “Ms. Jackson Effect.”

Thick raindrops glow clear in the Scott’s headlights and we are riding “Flagpole Sitta” to the end of the Earth, or at least well past Redding, and all the memorable lyrics come back to us. You know the words! Sing along…

Something something something something I feel a little bit naughty…something something

Something something something something…you know it never does!

Ahhhhhhh I’m not sick, but I’m not well!

And I’m so hot

Cause I’m in Helllllllllll

Something something something something mirror something see a little bit clearer

something something and I don’t even own a TV

something

Uhhh

They cut off my legs now I’m an amputee God Damn You!

Ahhhhhhh I’m not sick, but I’m not well!

And I’m so hot

Cause I’m in Helllllllllll

Those top notch backing vocals kick in. Sing it inside your own minivan and see how awake you’ll stay, it works! I’m in the back seat behind Ryan, who’s driving. Next to me is Ian, and Will is riding shotgun. We reach the bridge and ooh baby this song has a really, really good bridge.

I wanna publish zines, and rage against machines

I wanna pierce my tongue, it doesn’t hurt it feels fine

The rain is really coming down now. The great song’s great bridge keeps climbing up. The band swells and the drums hit a steady triplet fill and a guitar pick slides down the fretboard like a jet engine rocketing all of us and the world beyond into the final verse with impossible force.

Paranoia, paranoia everybody’s coming to get me!

“Fuck,” says Ryan, as we drive into a very large puddle in the center of the highway.

And my minivan spins. We are oddly calm as we spin. I grip the sides of my seat, wedged between gear and merch and snacks and the people I love being around, and I see water rushing up the windows on either side of us. We stop spinning and come to terms with our new foundation. We’re facing the wrong direction on the highway inside a minivan that has just performed a clean 180-degree turn. We were driving in the left lane of a two-lane road, and a body of water had flooded across both lanes of the highway at the point where we drove across at full speed and hydroplaned into our current position in the slow lane, facing the wrong direction.

{Insert diagram of car and road here or allow the reader’s imagination to do the heavy lifting}

We take a moment to assess that everyone is okay. The engine has flooded and shut off, but the car still has power. Will yells, “turn off the music!” We interrupt Harvey Danger from sailing through their final chorus. Someone presses the plastic button next to the radio directing our hazard lights to flash on and off and on and off. I slide open my door and there is a river next to the vehicle on the side of the road, rushing by at least a foot deep. We are shaken and we aren’t sure what to do. I try to call AAA but the phone just keeps ringing. They probably knew it was bad news and didn’t want to pick up. A few cars slow down to ask if we’re alright, but no one really knows how to help us. We can’t stay put in the minivan or we will eventually be hit by a truck. We can’t leave the car because it’s wet and dark outside and we don’t much want to stand there and watch a truck hit the minivan while we catch pneumonia.

Across the aisle from me, Ian opens his door facing the other side of the highway and we can see the asphalt surface of the road, revealing that only one side of our vehicle is in deep water. Ryan tries to start Scott’s engine, and it turns on. Praise be Scott! Kneel before Scott! Carefully turning towards the dry land, Ryan is able to right our direction and we drive the remaining two hours in silence.

The next day is not the day off we had dreamed of, but we’re lucky to have it. We sleep in. When the van spun, my opened bag of peanut butter-filled pretzels exploded all over the floor, so I quietly head to the car wash and get Scott a shower and a shave. We call our moms who tell us they love us and are glad we’re alive. We call our dads, who explain safe driving.

On that day and the days that follow, we wobble around the “what ifs.” If any car had been right behind us, we would have spun into them and been in much worse shape. If we had hydro-planed an hour earlier, we might have died alongside a much more embarrassing swan song.

What if we crashed to Dave Matthews Band’s “Crash?”

What if the officer called to the scene assessed the situation, turned to his partner and said: “At least they died doing what they loved…listening to ska.”

What if we weren’t so lucky?

Our tour continues and we do a much better job of facing the right direction as we drive. Weeks later, we reach Nashville. I get dropped off at Jessi’s house and I tell her the Saga of Scott & The Harvey Danger 180. She laughs. She coughs. She has chemotherapy the next day and has to miss our show, but she insists on wearing a Landlady t-shirt into chemo, and I wear one of Jessi’s “Ain’t Afraid” shirts at our show, even though when I’m wearing it I know it’s a lie. We stay up late making jokes and I fall asleep on her couch. My band picks me up the next day and we go to the venue in East Nashville. I explode on the stage and try my best to swirl pain into magic into joy.

Tour finally ends as it always finally does and when we return, Tour Brain goes into hibernation. Life goes on, spring and summer come and leave, and just before fall, I get a phone call, and my gut braces my heart. I’m told Jessi is on the way out, this week, for keeps. I fly to Nashville to say goodbye, buying a ticket as soon as I hang up, from the airport to the hospital.

I didn’t think these would be the rock & roll memories I’d remember.

On the first Those Darlins tour, Jeff played drums and I played keys and saxophone. We traveled in their old tiny blue van, and before the first show in Pittsburgh the only side door stopped opening. We all had to get in and out by climbing through the front. Driving to the second show, we noticed the passenger-side front wheel began to feel a little “falling-offy.” Moments later, on the highway, the wheel did indeed fall off the van, and we were stuck looking for a tow truck that could fit five passengers on a Sunday and get us back to New York City where we could trade their van out for mine and finish the tour. Luckily I had a shiny new AAA card which awarded us one hundred miles of free towing at a time, so we would get towed one hundred miles, then call AAA again and say we’ve broken down and get a new truck to bring us one hundred more miles, and carried on that way until we made it to Brooklyn at four in the morning. It was all worth it to get to play great songs.

Jessi wrote such great songs. When she was on stage, you couldn’t turn away, and when she opened her mouth and her voice cut you in half, you couldn’t ignore or retreat. A hatchet blade with two sides and the lightness and the darkness were delivered with equal commitment. I was lucky to be in her orbit and rotate together through many rooms over many years, but I didn’t want it to end in a waiting room.

The waiting room has been taken over by our people, and it is not unlike the moving minivan. Life is going on and it can’t be stopped but right here right now we are safe, together, killing the time it takes for Jessi to get from Seattle to San Francisco. We are taking turns lightening the load, making jokes and fetching snacks and sharing the space with people who all understand. We are the same and we will support each other, even as the darkness chisels through.

We take turns going in to see Jessi. She is on morphine and I can’t quite tell if Jessi’s really aware of what I’m saying to her, but I keep saying it anyway. I don’t know what I say, and its rambling and uncertain, and as I inch close to her bed in my chair, Jessi tells me to be quiet, for once, and I laugh so hard that I cry.

I come out, and I wait, and we wait.

A few days later, the day that Jessi died, I missed it when it happened. I was downstairs in the hospital lobby, surrounded by plants and playing Hearts, making life go on with Kyshona and Larissa who would sing Big Star with me a few days later at Jessi’s memorial service. A close friend came downstairs and offhandedly mentioned how Jessi was gone now, thinking that we already knew. We didn’t know. But now we did. Jessi had died. It was so surprising it was almost funny, to miss out on that sour moment of knowing the second that it had happened, and I think that maybe it’s good luck. I can find some gratitude within grief and I can convince myself to believe it.

The following morning, I wake up in bed at Linwood’s house and it wasn’t a dream. Jessi is gone, and unlike when Terry died I am not with my band. I have no performance that night, no scheduled power outlet of feelings and electricity. Without it, I am unsure. Without Jessi, I am broken. So I stay in bed, and I cry. And it feels incredible. And it never really stops.

Losing these people from my life is an immovable pain, a never-softening hardness. But the hardest experiences stick with me because they’re so often cemented to the people I’ve gotten through them with, the people who make any tear feel wearable, the people who teach you not to take anything too seriously. Even when you’re spinning on the highway. Even if they don’t all make it to the end of the story.

Sure, this is about what was once inseparable being torn away, dramatic and true. But this story is also about how the mundane can get us through nearly anything. The time-killers, the card games and mixtapes on MiniDaiscs and songs on car stereos and snacks and jokes and farts, the ways of dealing with the moments in time that sometimes you wish you could skip over but in retrospect would never forget for any amount of money, not even in exchange for your times tables. Great songs don’t exist in a vacuum and neither do we. The magic of meeting the right people and the right moments and making music and sharing air is irrevocably tied to the more boring components of our journeys. It all adds up, making the myths more realistic, the expectations less impossible, and my memories of these practical paths will allow me to love and play again, even though I know it could still end in pain and loss.

Which leads me back, romantically, to merch. The rock & roll memories I wanted to remember involved a different level of success for myself. And that can be the fastest lane for beating yourself up, a crowded space that takes all comers who believe they should be doing just a bit better than they currently are. I thought perhaps by now I would be playing for thousands of people. I thought perhaps by now I’d be leaving fans waiting at an autograph signing because our plane landed late and we had to make the show. I certainly expected a bigger van than the one I grew up driving around in, and I definitely planned on selling more records than I currently do.

However. When we spun around on the flooded highway cranking “Flagpole Sitta” by Harvey Danger, we should have tipped over. My people and I, we should have died. But despite the speed at which we drove into the water, our vehicle was so completely weighed down by unsold merch that the minivan remained upright. The heaviness of those boxes and boxes of LPs and CDs, esoteric nonsense of the past, dreams unfulfilled although there’s always the next show, that heaviness pushed our wheels down and kept our futures intact.

That merch saved our lives. Maybe optimistic dreaming is a habit worth keeping around, even after my minivan is dead and gone.

—

“What you want from me is a lost memory, of time that I spent thinking how lucky are we” – Terry Adams, The Teenage Prayers, “Dreams of the South”

“They all say go go go, they all say knock ‘em dead, but when I took the reins they all chop off my head” – Jessi Zazu Wariner, Those Darlins, “Optimist”

“Rock & roll is here to stay, come inside where it’s okay, and I’ll shake you” – Alex Chilton, Big Star, “Thirteen”

“I feel like I’ve seen just about a million sunsets, she said if you’re with me I’ll never go away” – Arthur Lee, Love, “Everybody’s Gotta Live”